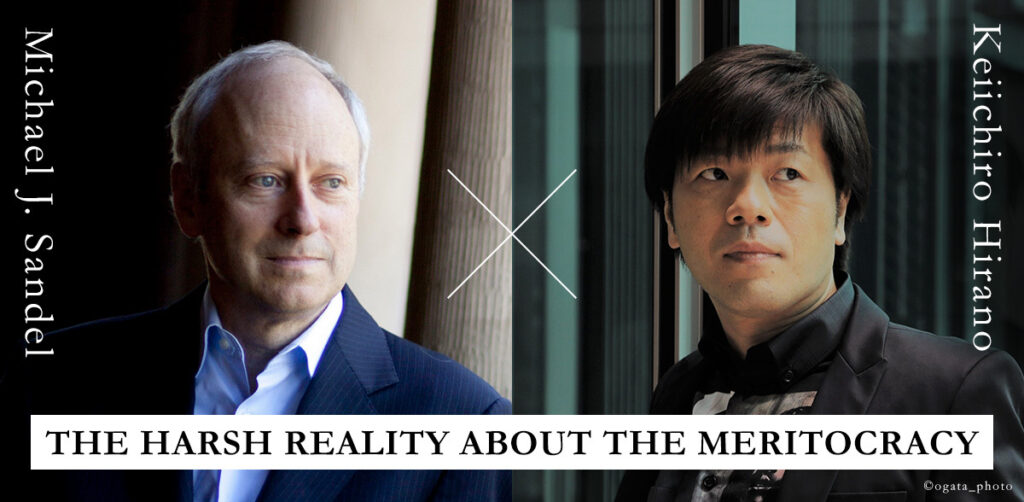

HuffPost Japan put up the article of Keiichiro Hirano’s discussion with Professor Michael Sandel. This is an extract of that.

A political philosopher and Harvard professor Michael Sandel whose latest book is “The Tyranny of Merit″ gave a special talk for HuffPost Japan on the problems behind the “meritocratic society,” which emphasizes one’s effort and results, and the self-responsibility theory prevalent in Japanese society. The interlocutor was Keiichiro Hirano.

They discuss everything from meritocracy to self-accountability to the pros and cons of lotteries to Shohei Ohtani. They touch on Hirano’s book “At the End of the Matinee” as well.

In this article, the script of the dialogue between Professor Sandel and Mr. Hirano is available.

▼Click here for the full text.

Professor Michael Sandel speaks to the Japanese reader – The harsh reality about the meritocracy

Self-responsibility and Meritocracy

Hirano:

Hi. Author Keiichiro Hirano here.

Today, we’ve invited Professor Michael Sandel to talk with me about his much-discussed new book, The Tyranny of Merit : What’s Become of the Common Good ? This book is selling very well.One of the organizers just told me that it has already sold over 80,000 copies here.

It takes up many topics near and dear to us such as meritocracy and the self-responsibility narrative. This book is so important that I think all Japanese people should read it.

Without further ado, I’d like to bring on Professor Michael Sandel.

Hi, Professor Sandel,

Sandel:

Hello. It’s good to be with you, Mr. Hirano.

Hirano:

So, Professor Sandel,

Where are you speaking to us from today?

Sandel:

I’m joining from Madrid in Spain, where my wife and I are spending some time doing some writing, seeing friends and enjoying the beautiful Spanish setting and sunshine.

Hirano:

I see. Let’s jump right into the discussion.

I’d like to begin by giving you my impressions of the book. It touches on issues that are deeply relevant to Japan. The past 30 years has seen ongoing discussion here about the narrative of self-responsibility and the need for social esteem under the influence of neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism is a global current and I recognized that the self-responsibility narrative stemmed from it. Nevertheless, I had come to believe somehow that the problems this narrative posed were Japan specific.

When discussing this self-responsibility narrative overseas,I wasn’t sure how to translate it, and some people told me it was unique to Japan. This book analyzes the issue so clearly and comprehensively through the lens of meritocracy that almost nothing else remains to be said. It brings renewed recognition that the issue causes significant problems in America and Europe as well.

To explain the situation in Japan a bit more, we have been experiencing a period of economic stagnation, since the financial bubble burst, that many call the Lost Three Decades. Neoliberal policies have been promoted throughout and inequality has steadily spread. The affluent came to be called winners and the rest losers.

Rhetoric defending the winners was especially prevalent in the 2000s. The affluent were said to deserve what they had because they were harder working and more diligent while many assumed that the poor would amount to nothing if left to their own devices because they were lazy.

I have referred to this as a rhetoric of “cold, passive dismissal.”

This period was followed by the Global Financial Crisis. Social movements arose in response such as the Dispatch Workers’ New Year Village. Such developments brought visibility to the hidden class of precarious laborers in poverty.

Next came the 3.11 Great East Japan Earthquake. This triggered an upsurge in nationalism centered around overcoming this calamity. Others reacted to this by asking what it might mean to be Japanese. Then a new theory came into prominence that aimed to sort Japanese people according to those who deserved publicly funded relief and those who didn’t.

Soon Japan’s fiscal crisis was on everyone’s mind and a discussion unfolded about who and who was not worth bailing out with taxpayers’ money. For example, some argued for denial of welfare to those in poverty due to laziness, or for denial of medical insurance to those with diabetes due to an unbalanced diet. Recipients of government support were routinely criticized for placing a burden on everyone else.

I contrast this rhetoric of “heated, active dismissal” to the “cold, passive dismissal” in the 2000s.

Such meritocracy does extreme harm to the dignity of those struggling socially. The fantastic analysis in your book fits all this perfectly.

Now, one’s profession is crucial in Japan to how you are ranked socially. With employment conditions unstable, this has plunged many into an identity crisis.My generation, The Lost Generation, has been especially prone to this hazard.

We are currently in and around our forties and we graduated from college just when economic opportunities were evaporating. It was nearly impossible for many of us to find employment. Since then the job opportunities have remained few and far between for them.

Under the narrative of self-responsibility, my generation has sustained deep scars from being continuously told we are to blame. We have fought back by rejecting this claim, and identifying the problem as a social ill.

So Professor Sandel. In The Tyranny of Merit, you make various arguments concerning meritocracy. Would you mind telling readers in Japan which point you most wanted to emphasize?

Sandel:

Well, thank you for giving me the Japanese context for this discussion of meritocracy, Mr. Hirano. I find it very interesting.

And the account you have given, the situation in Japan in regard to work, and in regard to the divide between winners and losers, and also the notion of self-responsibility, there are some parallels with what I’ve observed in the United States and in Europe.

In recent decades, the divide between winners and losers has been deepening, poisoning our politics, driving us apart, eroding the social bonds that hold societies together.

This divide between winners and losers has partly to do with widening inequalities in recent decades. But it has also to do, I think, with changing attitudes towards success.

Those who have landed on top in this period of globalization, those who’ve landed on top have come to believe that their success is their own doing.

Then they therefore deserve all of the benefits that the market keeps upon it. They also tend to believe, the winners tend to believe, that those left behind those who struggle must deserve their fate as well. This is the harsh side of meritocracy.

Meritocracy, in principle, seems like a noble ideal. Meritocracy says that if chances are equal, the winners deserve their winnings. But the harsh side, the dark side of this meritocratic principle connects very directly, with what you said about self-responsibility.

Self responsibility is an attractive idea for the winners because it enables the winners to say, I’ve earned it, my success is my own doing. I am self made and self sufficient, and therefore I deserve all the benefits that flow from success.

But it’s a harsh principle, when applied to those who struggle to those who’ve been left behind by unstable work, and hard economic circumstances, because it tells those who’ve been left behind, your failure is your fault. It’s your own responsibility.

So the result is that meritocracy generates among the winners, a kind of hubris, lack of humility, a belief that they have achieved everything that they’ve achieved on their own hubris among the winners and humiliation among those who have been left behind.

And it’s this divide between winners and losers, the harsh judgments about who succeeds and who struggles that, I think, is pulling our societies hard and eroding the social fabric.

I see this in the United States. I see this in Europe. And based on what you’ve described, about the situation in Japan, I see certain parallels. What do you think, Mr.Hirano?

The story behind Shohei Otani’s success

Hirano:

What you said suggests that meritocracy is not only very attractive but might in some sense come naturally to humans.

For example, imagine several people together. When one does something, the others see that he is terrible at it.If someone better was present, they would want to take over the task. They might say that they should take over because they’re better at it. Or imagine there are two people who can perform the task. Then they would discuss who might be better at it. If it turns out that one is better and they take over the task, then things might go well. In that case, everyone is better off. Such negotiations arise all too naturally.

I suspect that meritocracy on a societal scale is just an extension of this. Imagine someone incompetent in government or a company president who is a complete hack. I might want to take over for them. Or imagine someone incompetent in government. I might want to take over for them. Or imagine a company president who is a complete hack. I might want to take his place.

One problem is the specialization of professions. This binds meritocracy up with what we might call academocracy. This has become a significant cause of discrimination.

On a somewhat unrelated note, I think the lyrics of rap music are highly meritocratic. In my novel “At the End of the Matinee”, I mentioned “Empire State of Mind” by Jay-Z. This track is about being in New York and rising from rags to riches and idealizes New York as a city that makes anyone’s dream come true. In one scene from the novel, a female character living in New York hears this track and becomes incredibly depressed.

Another example is YouTube. Popular YouTubers invariably respond by describing the hard work of uploading a video every day when they are derided for earning money through this platform. They emphasize this in a very meritocratic way.

So, Professor Sandel. You are highly critical of tying academic ability to the evaluation of a person. But do you also recognize that meritocracy is better than a lot of systems out there in some ways?

Is your position that it is a necessary evil that cannot be entirely rejected?

Sandel:

Well, you’ve raised a fascinating question that goes right to the heart of this issue. I agree with you, Mr. Hirano, that merit in the sense of having competent people fill jobs and social roles, competence is a good thing.

If I need a surgery performed, I want a well-qualified surgeon to perform it. If I’m flying in an airplane, I want a well-qualified pilot to be at the controls of the airplane. So of course we want competent people to be assigned to the jobs and social roles that they will perform well.

Problem arises when the system of values and the way we regard success becomes entangled with, bound up with the allocation of social roles to those who can perform them well. And this goes to the point you raised, Mr. Hirano, about effort. What enables someone to perform well in a job or social role may have partly to do with effort and practice and training, and that’s important. But it’s a mistake to assume that effort is everything.

Consider a great athlete. Now, I’m a baseball fan and I’m a great fan of Shohei Otani. I think he’s one of the greatest baseball players in the history of baseball.

Now how did he become such a great baseball player? He certainly practiced from a young age. He trained, he worked hard, he devoted effort. That’s true. Both to pitching and to hitting, which is the remarkable thing.

But I played baseball and practiced baseball from a very young age. I loved to play baseball. I played it for hours and hours. I could practice baseball 24 hours a day and never be as great a baseball player as Shohei Otani. Because in addition to his effort, he has remarkable athletic gifts. Those gifts are a blessing or a good fortune.

So it’s a mistake to think that effort alone is the basis of being good or successful at various jobs or social roles. And it’s especially a mistake to assume that because someone is gifted or talented, and therefore successful, that their gifts or their talents are the result of their own doing. We sometimes tend to assume this, but it’s a mistake.

And consider this. Not only is it a matter of good luck that V has great athletic gifts for pitching and for hitting. It’s also his luck, his good fortune, not his own doing, that he lives at a time when people love baseball and reward it and value it at a very high level.

If Shohei Otani had lived during the days of the Italian Renaissance, they weren’t very interested in baseball back then. They would not have rewarded him the way we reward him today. They cared more about fresco painters than about baseball.

So the fact that we have this or that gift or talent, that’s not our doing. That’s not our self-responsibility. That’s our good luck. And the fact that we happen to live in a time and in a society that values and rewards the talents we happen to have, that also is not our own doing. That also is not our self-responsibility.

This is why I think that in meritocratic societies like ours, the successful need greater humility. The kind of humility that comes from recognizing the role of luck and good fortune in cultivating our talents, in having those talents in the first place and in living at a time that prizes and honors and rewards the talent we happen to have. So for all of these reasons, I think the successful especially need to question their hubris, their tendency to believe that their success is their own doing.

Recognize the role of luck in life and therefore have a more humble attitude for the talents and gifts that we happen to have. And with that greater humility, I think comes a greater sense of responsibility for all of our fellow citizens who may be talented in different ways, who may have lesser achievements, but who nonetheless make important contributions to the lives we live together.

Does that make sense? Do you think?

Hirano:

Right. I strongly agree. Japan hosted the Olympics recently. Most people recognize Olympic athletes as special, but when they watch Paralympic athletes, they feel like all disabled people might achieve the same with enough effort. People even try to encourage them to do so.

But there was a newspaper article arguing that disabled people are not all the same, and that being told otherwise can be a source of pressure that leads them to suffer. Since we have come to the topic of luck, let’s discuss how you see us moving beyond meritocracy.

▼Click here for the full text

Professor Michael Sandel speaks to the Japanese reader – The harsh reality about the meritocracy